Empathy at work is absolutely essential. We all suffer. Suffering is inevitable, and members of organisations suffer. We suffer for personal reasons (the death of a loved one, the problems of a child, a break-up) and we suffer for professional reasons (tension, tiredness, stress, incomprehension). Just as an example, the lack of good support during a colleague’s grief over the death of someone close to them costs organisations more than 75 billion a year. There are many trends in the labour market, but we must never lose sight of the fact that empathy must be worked on at work to create a more compassionate environment.

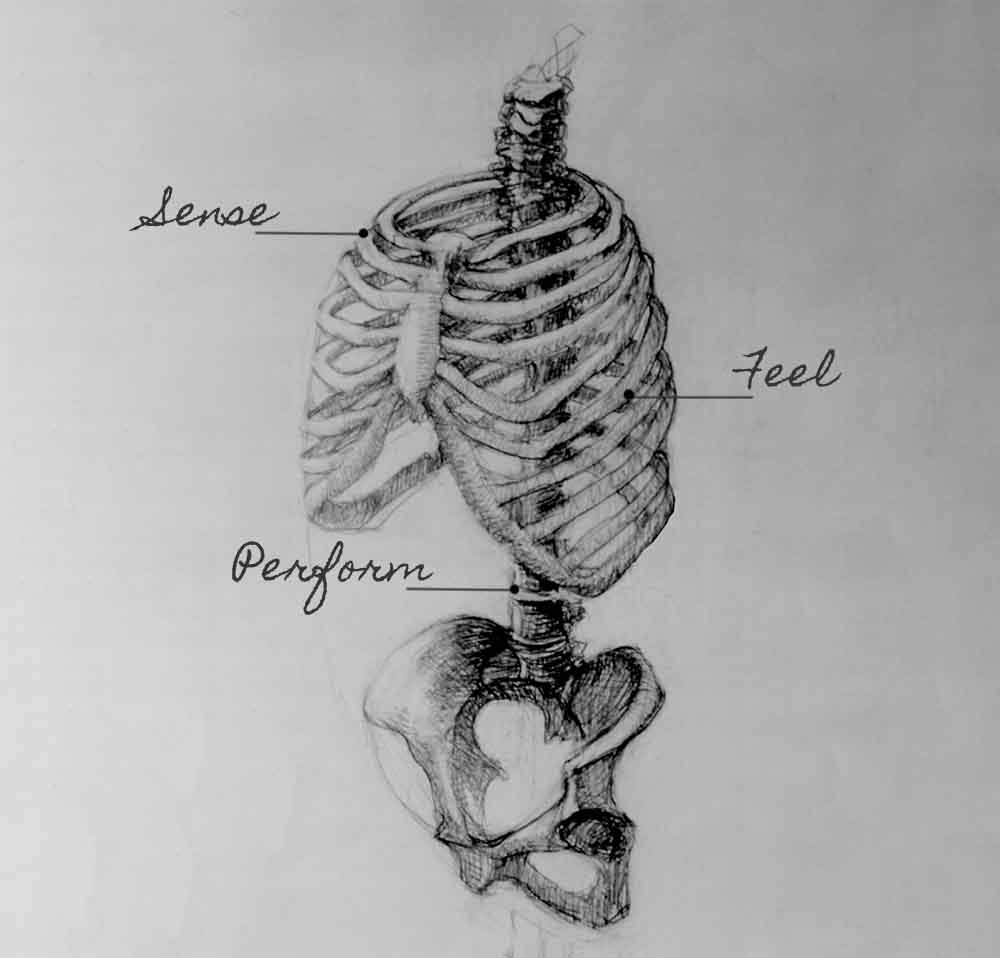

One of the ways to alleviate the suffering perceived in others is through compassion. The word compassion comes from the Latin cumpassio, and literally means “to suffer together”. For compassion to exist, at least three steps are necessary: 1) realizing that the other is suffering, 2) feeling that the other’s suffering matters to me, and 3) acting to reduce the suffering. In summary, the anatomy of compassion would be to perceive, feel and act.

How being empathetic at work benefits everyone

Nowadays, we talk little about compassion at work. It seems, in fact, that it is unprofessional to talk about compassion and empathy in the workplace. However, according to recent studies, compassion and empathy at work have a positive impact on the person who suffers, the person who accompanies, the observers, and the organisation itself. Among other evidence, it has been shown that compassion at work generates more commitment from the person who has suffered, more job satisfaction for the person who accompanies, an increased sense of relevance from observers of the act of compassion, and less intention to leave the company in general (Dutton, Workman, & Hardin, 2014; Dutton, Worline, Frost, & Lilius, 2006; Lilius et al., 2008). However, compassion tends to be personal, from one person to another. Therefore, if it is personal, and depends on the goodwill of individuals, what role do organisations play? Can organisations limit or facilitate individual compassion? Can organisations limit human compassion or become contexts that systematically facilitate compassion? How can one be empathetic in a workplace where compassion is limited?