What am I going to read about in this article?

- Types of equality measures

- Policies that impede equality

- Policies that allow for equality but do not promote it

- Policies that promote equality

- How to promote effective equality policies?

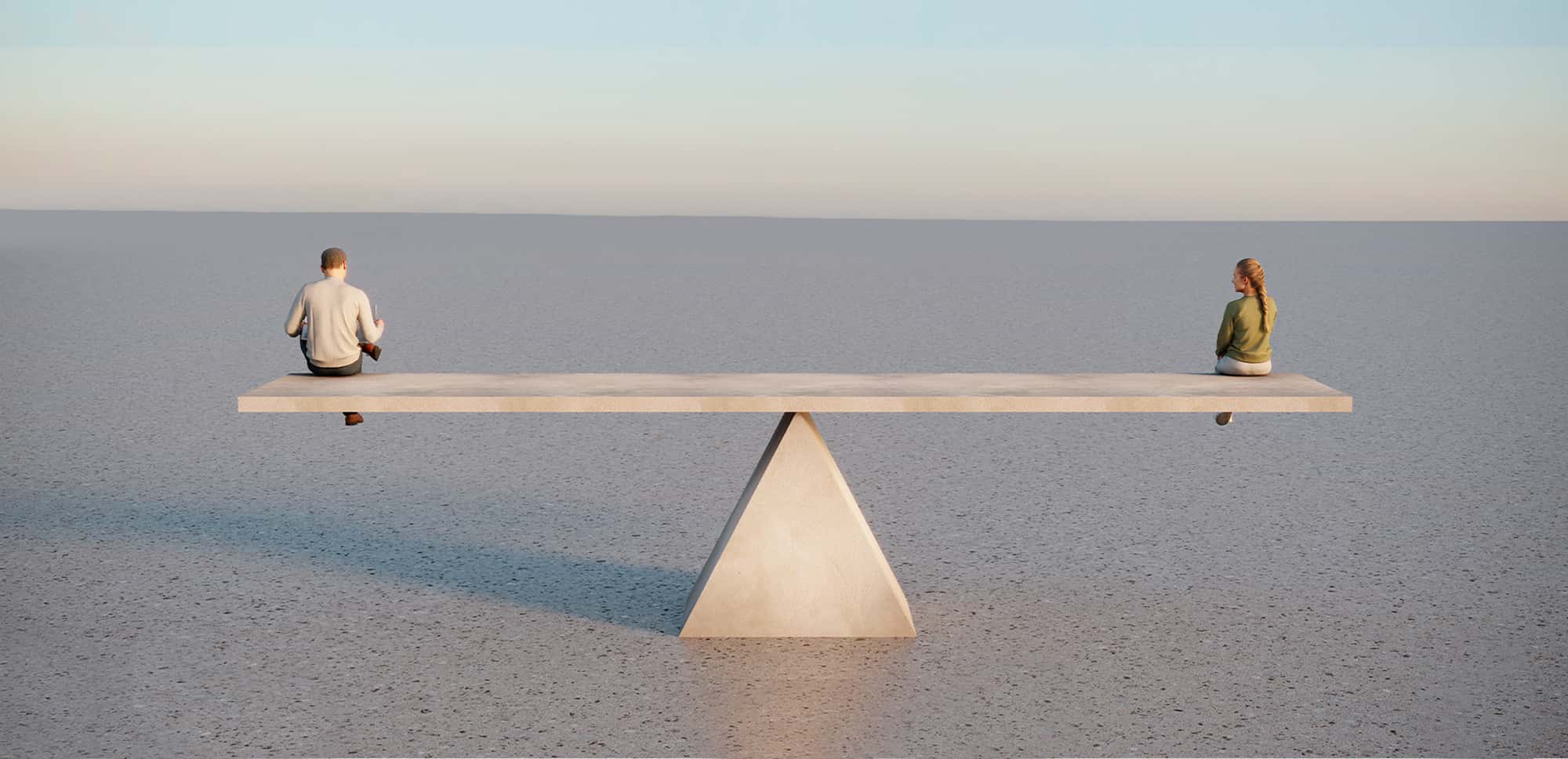

For some time now, the prevailing normality has been that of couples where both members work. Faced with this new situation, whether by will or by necessity, there are many initiatives and voices that propose the design of institutions and equality policies that support these families, where both parents have work and family responsibilities.

This proposal should, on the one hand, promote women’s full access to the labour market and, on the other, the full incorporation of men in the care of the home and family (Gornick & Meyers, 2003). Basically, the idea is to encourage each group to join the sphere where they are least present or where it’s most difficult for them to develop fully so that, once the entry barriers have been cleared, they can grow freely wherever they prefer.

Measures that favour equality (and others that don't so much)

Equality policies are a good solution, and have been applied in both the political and organisational fields through public policies, and private flexibility policies. However, Brighouse and Olin Wright (2008) warn us that not all equality policies and support policies for dual-income families favour equality; moreover, some even prevent it.

To this end, they use the example of parental leave. According to their analysis, equality policies could be classified into three groups, ranging from the most lukewarm to the most radical and controversial proposals, which for the moment are no more than a narrative for reflection.

Policies that hinder equality

Some policies of equality and support for dual-earner couples may, paradoxically, actively contribute to maintaining inequality in the division of domestic and family tasks. Exclusive care leave for mothers is one example, according to the authors, as it dictates who should care and who should work.

However, they also point out that unpaid parental leave, even if neutral and allowing free use by either parent, runs the risk of hindering equality, as cultural inertia and the past eventually prevails.

The neutrality of politics will be undermined by culture. These two examples, maternity leave much more generous than paternity leave (as happens in Eastern European countries), or unpaid parental leave (as happens in Spain after the 16th week)[1], are positive in one sense, since they facilitate and can improve the quality of life of the mothers who take advantage of them, but at the same time they may not be sufficient to reduce inequalities in the division of labour, since in some way they favour the replication of the past.

Policies that allow for equality but do not promote it

The case of care policies, and more specifically parental leave, would comprise all highly paid parental leave (e.g., parental leave covering at least 80% of the salary). which by their very nature:

- (a) enable women to develop in the labour market and to have children.

- b) allow men, if families decide so, to also participate in care activities, by making use of said leave.

This type of equality policies is not offered to individuals, but to families; therefore, they become parental leave, not paternity or maternity leave. In a certain way, they’re understood and articulated as a right of the child, and not as a right of the worker or the parent. Such policies allow for egalitarian strategies at home, but without putting pressure on who should do what. As Brighouse and Olin Wright point out, the best European policies are of this nature.

Policies that promote equality.

These are policies that attempt to create incentives in order to put some pressure on families to move towards a more equal gender distribution of care within the family.

“Policies that promote equality seek to create incentives for families in order to move towards a more equal gender distribution of care within the family”.

There are moderate and radical versions. The paternity leave proposal, known as the “daddy quota” where the leave is exclusive and non-transferable for the father is a moderate version of these policies that promote equality. This proposal, which emerged a few decades ago in the Nordic countries and has recently landed in the Mediterranean culture, has an incentive character by causing that, if the father does not use the paid weeks, nobody will do (take-it or lose-it).

There are more radical versions. An example would be 3+3+3. The government offers three months maternity leave, three months paternity leave, and three months parental leave. The incentive again lies with the father, as parental leave (open to one of the two parents) will only be offered if the father uses paternity leave. Therefore, in a family where the father uses the policy, they will have 9 months of paid leave between both members, whereas if the father does not use it, they’ll be left with only the mother’s corresponding three months.

It is therefore in the father’s power to provide his newborn child 3 months with the parents, or 9. Brighhouse and Wright offer even more radical proposals, such as giving the mother as many days as the father uses. At the moment, however, no country has gone to this extreme.

How to promote effective equality policies?

Be that as it may, Brighouse and Wright’s analysis invites us to reflect on the real impact of the policies we articulate to enhance equality and improved well-being in dual-earner couples. At the organisational level, policies articulated by companies may suffer similar implications. Therefore, it would be interesting to reflect on:

- The real impact of neutral policies. Not everything that’s articulated as neutral has a neutral use. It’s important to measure who uses the policies we offer, and what their reasons are. Lack of legitimacy is very often one of the main reasons for non-use of neutral policies. In the case of men, many fathers perceive that the policies are not for them even though there’s a chance to take advantage of such benefits.

- The need, in some cases, to offer specific resources and programs for a group with different requirements. Following the logic of Brighouse and Wright, it’s often necessary to incentivize, in order to avoid reproducing previous schemes that you want to change. The incentive not only stimulates the incentivized to use what is offered, but even more interestingly, it enhances the legitimacy of such use.

The challenge will be for all social actors to find a way to support dual-income families with innovative policies that not only facilitate their well-being, but also allow them to freely organize their caregiving tasks. In this manner, each family can be encouraged to distribute the work in the way the deem necessary according to their specific circumstances, by deciding whether the father, the mother or both will bear the burden of care in the first months or years of life of the children in the family.

References

Brighouse, H., & Olin Wright, E. (2008). Strong Gender Egalitarianism. Politics & Society, 36(3), 360–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329208320566

Gornick, J., & Meyers, M. (2003). Families that work. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.