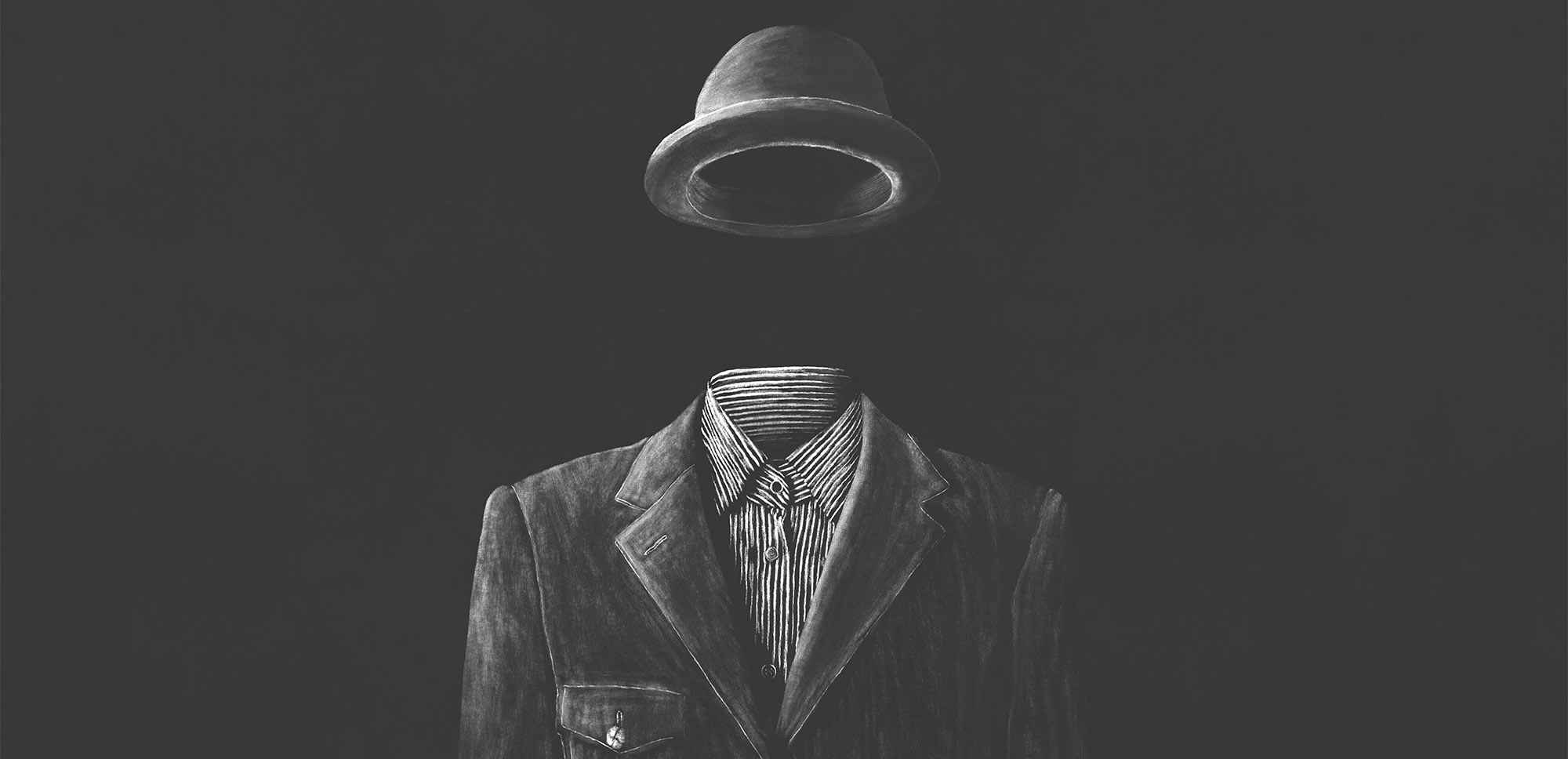

In a world where the five senses are our main tool for perceiving reality, we tend to believe in what we see. But what about what remains hidden from our eyes – does the unseen even exist?

Imagine that colleague at work who sometimes seems to be somewhere else, lost in thought. There are days when he barely says a word and, although he doesn’t take a minute for lunch, his productivity seems to stagnate. Perhaps this colleague is dealing with an invisible monster such as anxiety or an illness unknown to you that causes unbearable chronic pain.

Without an inclusive organisational culture, this partner may choose to keep their struggle silent. From our perspective we may not understand their behaviour, and may even misjudge them. Such situations can affect those living with invisible, permanent disabilities.

What will I read in this article?

What are invisible disabilities?

Invisible disabilities are coming out of the shadows and demanding wider recognition. Unlike physical disabilities, which can be easily identified by visible signs such as a wheelchair or a cane, these hidden disabilities go unnoticed by society.

According to the Invisible Disabilities Association, these conditions, which range from symptoms such as debilitating pain, fatigue, dizziness, cognitive dysfunction, brain injuries, learning disabilities and mental health disorders, as well as hearing and visual impairments, are as real and impactful as their physical counterparts. However, the lack of visible signs can lead to misunderstanding, stigmatisation and a lack of adequate support.

This, in turn, leads to hasty judgements and discrimination, creating additional barriers for those who are already coping with the difficulties inherent in their situation.

What percentage of disabilities are considered invisible?

According to the World Health Organisation, we find ourselves in a world where one billion people live with some form of disability. In a surprising twist, a US survey revealed that 74% of these people do not rely on a wheelchair or any other device that visually manifests their disability to the world.

“74% of people with disabilities are not dependent on a wheelchair or any other device that visually manifests their disability to the world”.

The “problem” of not looking disabled: making visible the invisible

Harvard Business Review has published the results of a study aimed at understanding the needs of people with long-term invisible disabilities. Researchers found that these people often feel excluded at work and are likely to receive fewer benefits or less access to training and promotions.

There’s a fear of the possible consequences for someone disclosing that they have a disability. Especially if the person they tell is their future employers. They’re persecuted by absenteeism and low productivity, when in the end they’re just people with special needs in terms of work-life balance, health, accessibility, etc.

“People with invisible disabilities often feel excluded at work and are likely to receive fewer benefits or less access to training and promotion”.

HBR’s research also revealed that leaders are not aware of the needs of people with invisible disabilities and are often not prepared to provide the necessary support and accommodations. But they also underline that there’s a real opportunity for new leaders to drive change in organisations by increasing their awareness and exercising more empathetic leadership. In this way, they can promote diversity and ensure that differences are valued and understood, not feared or judged.

People with invisible disabilities bring a wealth of unique experiences and skills to the workplace, and it’s essential that they’re recognised and supported appropriately. Every organisation has a responsibility and an opportunity to foster a supportive and empathetic work environment where all differences are valued and understood. It’s time we all open our eyes to see diversity in all its forms and learn to appreciate it, for it is this variety that truly enriches and strengthens our working communities.

Sources: