Give it a try. Choose the report you prefer, look at the year you want, and see which countries are the best to live in or who tops the ranking of the countries with the best quality of life in Europe. Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, Finland… the Scandinavian countries tend to top the rankings in terms of Work-Life Balance. Sometimes the Danes rank higher than the Swedes, or the Finns slip in between, but their dominance is overwhelming. And neither is an economic or military superpower, nor do they have much geopolitical clout. On the contrary, Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece are several steps down.

But if the pattern has been repeating itself for so many years, why don’t the caboose countries take note and copy what their neighbours do so well until they knock them off the podium? Therein lies the key to failure. Not everything depends on the measures to be implemented. Nor does it depend on compacting the working day, deciding on parental leave, or changing taxation.

Obviously, any benefit in each of these areas helps to move towards a balance between personal and professional life, which is influenced by factors such as the average number of hours worked per day, the time dedicated to leisure or the total number of public holidays per year. But the crux of the matter is not in the laws passed by governments, nor in the measures taken by companies. It’s all about oneself.

How does individual responsibility affect the best countries to live in?

Individual responsibility is one of the hallmarks of Nordic societies. It ensures the development of Work-Life Balance by harmonising the distribution of efforts based on needs and not on whims or fashions.

Measures should not be copied from one system to another, but rather the model. And that, outside Scandinavia, means changing the system. Only in countries where the level of honesty is measured in terms of lost wallets returned by their inhabitants can this unwritten rule of ‘We won’t say what has to be done by whom, but let everyone decide’ be applied. And how does this work?

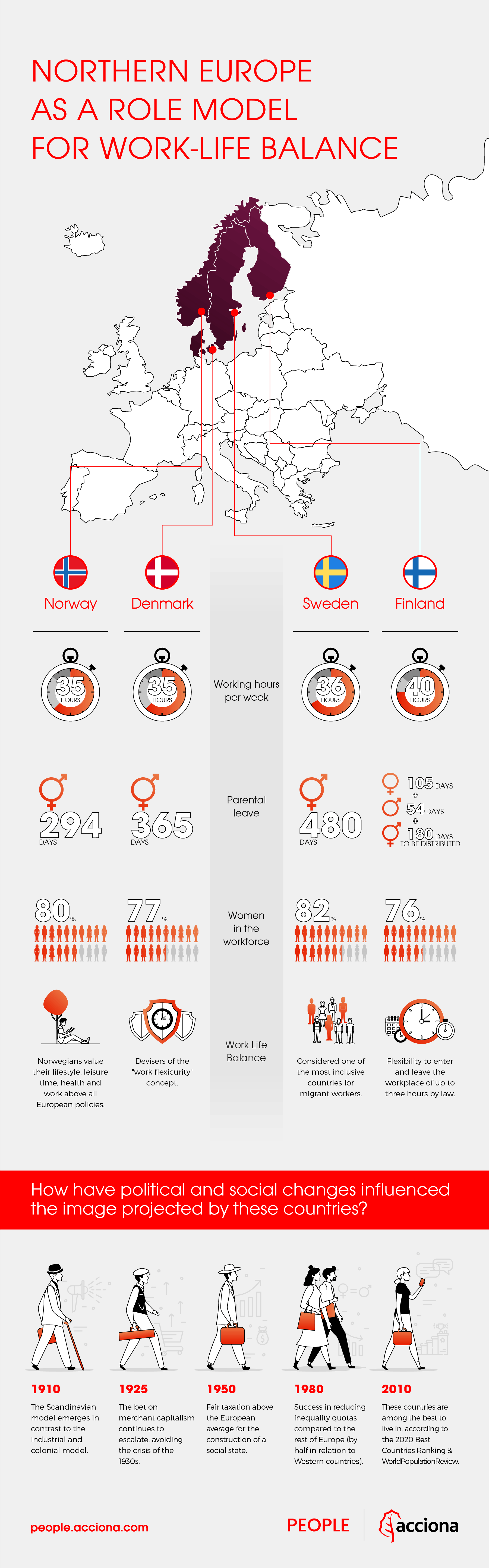

You only have to look at the paternity and maternity leaves granted in Europe to see that what we in Spain see as an achievement – the extension to 12 weeks for both – is nothing more than a backward step in relation to what is happening in northern Europe where parents have maximum freedom to take this leave according to their criteria and needs. Up to a maximum of 480 days can be shared freely between the father and mother. Because the factor that conditions the equation is not the employee or the company, but the child.

The same is true of Finland’s impressive education system, with a degree of investment and teacher recruitment – overwhelmingly civil servants – from which all benefit, not just a few.

The different working hours in European countries can also be reviewed. According to data from the Organisation for Cooperation and Development (OECD), in Denmark and Norway they do not exceed 35 hours per week. In contrast, the average is 40 in Spain, although unpaid overtime should be added as well.

All the above is detrimental to flexibility. Professor Anna Ginès, an expert in labour law at ESADE Law School, X-rayed the sequence using data from the study ‘Analysis of an equation for business competitiveness’ by the Asepeyo mutual insurance companyand ARHOE:

“We are the country with the least amount of rest time between the end of the day and the start of the next, so reducing the workday will benefit employees by improving their rest time”.

According to this study, 88.2% of companies in Spain fully define their workers’ timetable, a figure that rises to 95.3% in Latvia – the country with the least flexibility – and falls to 44.8% in the case of Finland, where there is greater flexibility in terms of schedule. This freedom leads us seamlessly to the initial premise that circumscribes the success and development of Work-Life Balance around individual responsibility.

The challenge of involving politics, business and society

But the commitment must be a long-term one. This is not a matter of making an effort for a few years. The so-called Scandinavian model emerged more than 100 years ago, at the beginning of the last century, when the world was being reformulated after the industrial revolution. In the first half of the century, until the mid-1940s, public spending in Denmark or Sweden was lower than in France, Italy or even Spain. And look at it now. While neighbouring countries remained immersed in colonialism, Nordic countries opted for the modernisation offered by industrialisation by signing a great pact of the working classes to evolve within the capitalist system that allowed a gradual and sustained growth of wages which, in turn, normalises a tax burden of up to 60% in some recent passages.

It is thanks to this that Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland offer these numerous state aids in order to reconcile work and family life. It is therefore worth rethinking the classic question of “which country is better off?” for another in which politics, business and society- each from its own position- join in. What are you willing to do to make your country one of the best places to live and work?

Sources: L’Express, ResearchGate, IESE Insight, OECD